If it takes an early bird to catch the worm, what does it take to catch the bird? For Megan Roselli, master's student for the Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management (NREM) at Oklahoma State University, catching songbirds takes an even earlier wakeup call, a series of special nets, and a lot of patience.

Roselli and research technicians Dawn Brown and Liam Whiteman have spent the summer stretching their nets in and around Oklahoma City, an unlikely but productive study area. “Urban landscapes actually support a wide range of bird diversity,” said Roselli.

“We’ve caught 181 birds in the Metro area so far. We use mist nets – long, mesh nets that look a lot like a volleyball net – to catch birds as they’re flying to their next meal.”

Roselli carefully extracts songbirds, like this eastern phoebe, from a mist net as part of her research.

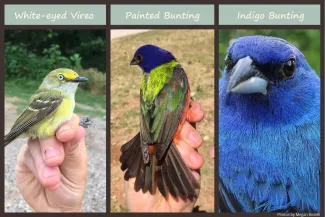

“Northern cardinals, Carolina wrens and American robins are some of our more common captures, but we’ve also caught several other species including white-eyed vireos, painted buntings and indigo buntings.”

While Roselli’s work mirrors traditional wildlife research – setting out nets to catch, identify and then attach a numbered leg band to a variety of songbirds – her team is expanding their research in a relatively new direction.

“We’re trying to understand the role of birds in tick dispersal,” said Roselli. “This could be one of many ways ticks and tick-borne diseases are moving around urban areas, coming into contact with high density human populations.” As urban areas sprawl into our forests, grasslands, and shrublands, the natural process of birds carrying ticks and other parasites is becoming of increasing concern to humans and human health.

This concept has caught the attention of the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology, primary funder of the study.

Roselli’s team, under the direction of Bruce Noden in OSU's Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology and Scott Loss in NREM, have been working this idea from two perspectives. Many Oklahoma City parks and nearby conservation areas, including the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation’s Arcadia Conservation Education Area, are being visited during the two-year study. There, birds are captured and examined for ticks and the surrounding habitat is “swept” for ticks.

“Birds live and thrive in environments where they inadvertently become involved in spreading ticks. Very few birds carry ticks and only a relatively small percentage of those ticks found on birds carry pathogens. It’s a risk, but a low one,” said Noden.

“About 12 percent of the birds we’ve captured and released have had ticks. A total of 33 ticks have been found on 22 individual birds,” said Roselli. “This low number isn’t surprising since birds regularly groom, or preen, themselves. We search the entire bird for ticks but find most where the birds would struggle to reach with their bill – around the neck, under the wing and near the thigh.”

Roselli has found most ticks in areas the birds would struggle to reach with their bills. A small tick was found on this female northern cardinal's underwing.

“We’re also trying to get a baseline of the number of ticks at our study sites,” said Roselli. “Dawn and Liam are baiting ticks with carbon dioxide traps and sweeping the surrounding vegetation with a flannel flag to catch ticks." These survey techniques have yielded an incredible number of ticks – more than 6,000 so far. “One trap held 731 individual ticks. We’ve exceeded our expectations for the first year of the study.”

Research technician Dawn Brown collects ticks with two methods; a carbon dioxide trap is set on the ground and a flannel flag is used to sweep the study area's vegetation.

“Several species of ticks have been found at each site; lone star ticks, Gulf Coast ticks, and dog or wood ticks are most common.” Adult ticks were primarily caught during the June surveys, but nymphs were more prevalent during the July sample period.

“This is one of the first projects of this type in the region,” said Scott Loss, Assistant Professor in NREM and project co-advisor for Roselli. “Everything we’re doing is new for the area.”

Though Roselli, Noden, and Loss are excited about breaking new ground in the Southern Great Plains, they are also trying to learn from other research efforts. “Outside of this region, several dozen studies have looked at the tick loads of songbirds,” said Loss. "We'll be able to compare our results to other areas of the U.S."

"With funding from the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology we're able to conduct a study that not only clarifies how the ecology of bird-tick interactions affects disease transmission cycles, but also to identify characteristics within and surrounding urban parks that influence the risk of humans transmitting tick-borne dieseases.”

Learn more about the project in this short video.

Minimizing Tick Exposure

To reduce the chance of a tickborne disease this summer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest repellent, showers and tick checks. Attached ticks should be removed as soon as they’re noticed by grasping the tick as close to the skin as possible and pulling the tick straight out. The CDC also recommends tumble drying clothes in a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to kill ticks.