“I’ve got a spot you might want to come see. But you ought to come soon.”

The cryptic phone call from now deceased Oklahoma Game Warden Dick James to Oklahoma Archaeological Survey researcher Leland Bement came in 1992 and was the beginning of an incredible archaeological discovery. Since that humble message 26 years ago, thousands of ancient bison bones left by Paleoindian hunters have been found at the present-day Hal and Fern Cooper WMA in northwestern Oklahoma.

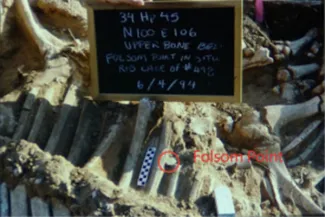

When Bement first arrived at the recently purchased conservation area, James pointed out a group of exposed bison bones in an eroded bank at the side of the Beaver River. Later, Bement returned to find a broken but distinctive Folsom projectile point that dates to more than 12,000 years ago. These surface artifacts eventually led to the excavation of three filled-in gullies or arroyos that has fundamentally increased our awareness of the hunting strategies of the second oldest culture known to North America.

It was during initial excavation efforts in 1993 that Bement and fellow archaeologists found clues ruling out the possibility the bones had been washed into the gully over time.

Leland Bement and crew at the Hal and Fern Cooper WMA excavation site.

“We took a cross section of the gully and found a lot of animals at the very end of that gully,” Bement said at a recent public lecture. “Amongst these bones we found more projectile points, many of which were embedded in the bison’s intact vertebrae and ribs. We believe all of these bison were run into a dead end gully where they were trapped and killed by a group of Folsom hunters.”

As the excavation continued, a second and third layer of bones that had been kicked, smashed, and stomped were found underneath the top layer of bones.

“These were trample marks. The bones found in the lower layers were already in the arroyo and got trampled by live animals being run into this arroyo.”

When archaeologists finished the excavation of the first site they had uncovered 78 animals and 33 projectile points from three distinct layers – representing three distinct kill events – within the arroyo. Sharp flake knives used to butcher the animals were also found among the bones.

Excavations of two additional arroyos located within a half mile of the first site have revealed similar, though independently intriguing, results.

“But we haven’t found evidence of extensive meat processing or of an encampment nearby.”

Based on the age and positioning of the bones, and an examination of the tooth enamel, a model of the Folsom hunting strategy has formed. It is believed the bison killed at the three excavation sites were migrating from New Mexico calving grounds to eastern Oklahoma wintering grounds. Groups of 30 to 60 bison cows, calves, and young bulls foraging in the fall along the Beaver River were selected by the Folsom hunters and driven into a dead end gully. When the lead animal reached the end of the gully and attempted to turn around, it and the rest of the herd became trapped. Hunters positioned at a safe vantage point along the upper rim of the gulley then threw spears, killing the animals. The bison were butchered within the arroyo, and cut marks on the bones indicate a gourmet butchering of the hump, ribs and tenderloins.

“We believe the animals were butchered while in the prone position, and the hunters were able to process about 50 percent of the meat. But it was the best 50 percent of the meat they could possibly get.”

Beyond deciphering this hunting and butchering strategy, Bement found an artifact that strongly indicates a social aspect of the kills.

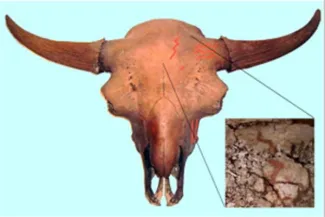

“I was uncovering a partially crushed skull and noticed a red zigzag line that looked like it was painted. I couldn’t believe what I was looking at.”

A bison skull, found at the Hal and Fern Cooper WMA site, is now believed to be the oldest painted object in North America.

The skull, now believed to be the oldest painted object in North America, had been placed at the end of the arroyo, positioned to look down at the incoming animals.

“This hints that this culture had hunting rituals and ceremonies that are associated at least with the hunting and probably other aspects of their gathering. The incoming herd trampled this skull, but the piece with the paint survived.”

After 25 years of discovery at Hal and Fern Cooper WMA, or the Cooper Site, where do the archaeologists plan to go from here?

“For me, I’m taking this scenario and moving it one step closer in time. Instead of the Folsom time period, I’m looking at what happened 9,000 years ago in the Oklahoma Panhandle where we have large-scale kills. Let’s see if we can rebuild this same sort of information out there.”

Fascinated with this discovery? Learn more in a series of posts to the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey’s Facebook page, listen to the full public lecture, or visit the Sam Noble Museum of Natural History’s Hall of the People of Oklahoma.

Visitation to the Hal and Fern Cooper WMA requires a valid hunting or fishing license or a conservation passport. Unauthorized removal of historical, cultural or archaeological artifacts from this or other lands managed by the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation is illegal.