Oklahomans live in an ecological melting pot where eastern plant and animal species unite with those typically found in the west. This diversity is especially evident in Oklahoma's bird populations.

Belted kingfisher.

The Checklist of Oklahoma Birds, compiled by the Oklahoma Ornithological Society's records committee, includes 473 species. The list starts with the tree-dwelling black-bellied whistling-duck, sorts through the 42 species of wood warblers documented in the state and ends with the weaver finches. While Oklahoma's sizable bird list can be explained by our state's diverse geography and vegetation, it may also reveal why bird and bird-related activities have stimulated our economy and affected our culture.

Biologists have separated Oklahoma into 12 distinct areas, or ecoregions, largely because of the differences in vegetation from east to west, and north to south. Because some bird species require specific habitats to nest or feed, the plant community can regulate the ecoregion in which these "specialists" can be found. Pinyon jays, aficionados of pinyon pine seeds, are just one example of a habitat specialist. Those birds use their straight bills to pry the pine seeds from the sticky cones and then cache them for later use. Because pinyon-juniper habitats are found only in Oklahoma's Panhandle, pinyon jays are restricted to that area. Similarly, the greater prairie-chicken requires large tracts of unbroken tallgrass prairie and is only found where those conditions remain. Other birds are less demanding and can nest and forage in a variety of habitat types. Northern mockingbirds are an example of a habitat generalist. These birds are common across the state and have actually increased their range because of human development.

Pinyon jays can be seen in Oklahoma's Panhandle.

Perhaps it's the sheer number of birds found in Oklahoma, the thrill of the hunt or the wonder of how long-distance migrants return to the same location year after year – the pursuit of birds undoubtedly influences our economy and way of life. Nationwide, 2.6 million people hunt migratory birds and spend more than $1.8 billion on equipment, travel, and lodging. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Harvest Information Program shows that at least 19,000 of those 2.6 million hunters are from Oklahoma. (An estimated 19,000 Oklahomans hunted mourning dove in 2014, while 18,000 hunted waterfowl.) Additionally, the National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation shows 773,000 people enjoy birdwatching around their home and on trips throughout Oklahoma each year. According to the survey, last updated in 2011, enthusiasts spent more than $198 million on wildlife-watching equipment. Over half of that total, $116 million, was spent on bird food, nest boxes and other bird-related supplies. The survey also shows Oklahomans spent an average of $159 on bird food each year.

Birds have inundated our culture. Most people associate the image of a mature bald eagle, our nation's bird, with freedom. The dove is a universal sign of peace. Bluebirds are symbolic of happiness, owls represent wisdom, and "little birds" are carriers of secret information.

These winged creatures can be found in the most remote corners of our state, in the busiest cities, and even on our mail. The first bird featured on a U.S. postage stamp was the bald eagle. Birds are also our mascots. Many Oklahoma sports fans cheer their teams to victory, all the way from the Fairland Owls in the northeast to the Sayre Eagles in the southwest.

While birds are obviously important to our society economically and culturally, they are also ecologically significant. Referred to as indicator species, birds often provide insights into the health of an ecosystem. Much the same way that canaries indicated unsafe gas levels to miners in the past, today's decline of sensitive bird species shows biologists which ecosystem is at risk and allows restoration activities to start before it is too late. One of the first steps in this conservation process, after realizing the specific living requirements of a species, is to take a count of the remaining population. This helps biologists prioritize tasks and focus on birds of greatest conservation need.

To help you navigate Oklahoma's bird life, we've compiled an assessment of the birds in six of Oklahoma's major ecoregions, with a special highlight on wetlands. In addition to listing the birds biologists are especially concerned with, each section points out the birding hotspots of the region, which birds to look for while exploring the region, and the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation's specific habitat management practices that benefit birds and other species. We hope this "bird's eye view" of the status of our bird populations reveals the remarkable wildlife viewing opportunities available in our state and provides incentive to get involved at any level.

- The Shortgrass Prairie

Jeremiah Zurenda

Jeremiah ZurendaA Glance at Our Driest Ecoregion

- Dominated by two low-growing grasses: blue grama and buffalograss.

- The most arid ecoregion; receives less than 21 inches of rain per year.

- Trees and woody plants are limited by droughty conditions.

- Once covering 1.3 million acres of Oklahoma, the shortgrass prairie region has been reduced to about 747,000 acres.

Birding Hotspots

- Black Mesa State Park

- Optima National Wildlife Refuge

- Beaver River Wildlife Management Area

What to Look For

- Burrowing owl

- Lark bunting

- Mountain bluebird

- Horned lark

- Western meadowlark

Status of the Shortgrass Prairie Birds

Because the shortgrass prairie only represents a small percentage of the state, many shortgrass-dwelling birds are challenged with habitat loss and large-scale changes. For instance, Oklahoma's burrowing owl population dipped below 1,000 birds after the prairie dog poisoning campaigns in the 1920s. In addition, conversion of breeding grounds to row-crops has led to the decline of several species in this ecoregion.

The shortgrass prairie serves as the eastern extent of several "western bird" ranges, allowing for several uncommon sightings.

Forty birds found in the shortgrass prairie region are species of greatest conservation need.

Threats to Shortgrass Prairie Birds

Nest Destruction/Disturbance: With a limited number of trees in the shortgrass prairie, many bird species construct nests on bare ground or in clumps of grass. Agricultural activities such as haying, mowing, and tilling can remove nesting habitat or unintentionally destroy nests. While using a flush bar can reduce the number of adults killed, planning activities around the nesting season is most beneficial to grassland birds. Nest disturbance is another threat. Species such as the mountain plover lay eggs on bare ground. Because eggs and young need to be protected from sun and heat exposure, displacing the incubating adult for as few as 15 minutes can lead to chick or embryo death.

Loss of Prairie Dog Towns: Several shortgrass bird species are linked to black-tailed prairie dog towns. Prairie dogs maintain complex burrows that can be used by nesting birds. They also keep surrounding grasses clipped short, allowing some birds such as the lesser prairie-chicken to perform breeding displays. Conserving these towns directly affects long-billed curlews, burrowing owls and a variety of reptiles.

Spotlight on Falconry

In the realm of hunting, falconry can be considered one of the most exciting field sports. Continuing in the ancient tradition of using trained birds of prey (falcons, eagles, hawks, and owls) to capture small mammals and game birds, falconers show us the strong bond that still exists between man and nature. Falconers were a large part of the peregrine falcon recovery process in the early 1970s. By 1968, the wild population was completely eradicated east of the Mississippi River. These sportsmen used their captive birds as breeding stock in the repopulation phase. As a result of combined conservation efforts, the peregrine falcon was removed from the endangered species list in 1999. To learn more about this type of hunting, go online to www.n-a-f-a.com.

Working for Wildlife: How the Wildlife Department Helps Birds

Technical Assistance: Private landowners can consult with the Wildlife Department about habitat management on their property. Department biologists can help landowners develop a management plan regardless of the wildlife objectives. For more information on private lands programs, go to wildlifedepartment.com

Playa Restoration: Playa lakes are an important water source for many birds in the shortgrass prairie. To protect these playas and provide habitat for birds, biologists plant native grasses around the perimeter or install fencing around the wetlands to limit livestock access. In some cases, excess silt is removed to restore the amount of water available for birds. For more information, check out the spotlight on playa lakes in this article's Highlight of Wetlands section.

Get Involved!

Sign up for our newsletter: "Your Side of the Fence" is a free newsletter designed for landowners and provides practical information to help manage the wildlife on private property. Subscribe today.

- The Mixed-grass Prairie

A Glance at One of Our Most "User-Friendly Ecoregions

- Dominated by two low-growing shrubs (sand sagebrush and mesquite) and two warm-season grasses (little bluestem and sideoats grama).

- Receives about 27 inches of precipitation annually.

- The dominant shrub in the northern mixed-grass prairie is sand sagebrush. In the southern half of the region, mesquite is the primary woody species.

Birding Hotspots

- Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge

- Sandy Sanders Wildlife Management Area

- Boiling Springs State Park

- Four Canyons Preserve

What to Look For

- Wild turkey

- Northern harrier

- Swainson's hawk

- Greater roadrunner

- Dickcissel

Status of the Mixed-grass Prairie Birds

The taller grasses of the mixed-grass prairie are compatible with a larger number of bird species than the shortgrass prairie. Even so, when brushy prairie is converted to agricultural fields, valuable brush is often bulldozed or sprayed. Without this important source of cover, many bird species suffer.

The northern bobwhite is closely tied to native brushy prairie and has seen an annual 2 percent decline in Oklahoma since 1966. In this same time period, the migratory Swainson's hawk has declined 1.64 percent.

Forty-eight species of birds found in the mixed-grass prairie are species of greatest conservation need.

Threats to Mixed-grass Prairie Birds

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Many populations of birds require large blocks of prime habitat to survive. When those habitat blocks shrink or are separated by developments, the remaining area will not be able to support the same number of animals. If the area becomes too small, birds may not be able to perform mating rituals or find sufficient food.

Altered Fire and Grazing Regimes: Maintaining grasslands requires a balance of fire and grazing. While both Greater roadrunner ning to be most effective. Heavy grazing and poorly-timed prescribed fires can result in low nesting cover and a reduction in woody escape cover. Biologists recommend grazing and burning about one-third of a property each year when managing for wildlife.

Spotlight on Black-capped Vireos

The Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in southwestern Oklahoma is home to the largest remaining population of the endangered black-capped vireo. This small bird has a black head, white "spectacles" and red eyes. Like most vireos, this bird sings a repertoire of specific notes or phrases and can be identified by song alone.

Refuge staff use a combination of grazing and prescribed burning to maintain the open, low-growing brush this bird needs for nesting. Other efforts include trapping brown-headed cowbirds to reduce the incidence of nest invasion. To learn more about nest invasion, or parasitism, check out the spotlight on brown-headed cowbirds in the Tallgrass Prairie section of this article.

After more than 30 years of recovery, the status of this endangered bird is more secure. Recent surveys show at least 3,300 pairs of black-capped vireos nest at the refuge.

Working for Wildlife: How the Wildlife Department Helps Birds

Maintenance of Bird Loafing Areas: Birds like northern bobwhite use low-growing woody structures during the day to avoid predators, summer's heat, and winter's frigid temperatures. Other birds, like northern harriers, focus on thickets while hunting. To maintain these areas, wildlife biologists disk around thickets 50 feet in diameter or smaller before conducting a prescribed burn. Disking helps protect the thicket from intense heat, limits the spread of larger thickets, and often encourages forbs.

Grazing Leases: The Wildlife Department often leases grazing opportunities on Wildlife Management Areas to manage native bunchgrasses. The cattle help manage the thatch layer by grazing and hoof action creates paths. Additionally, seed-producing plants are often abundant in areas where grazing is concentrated. Wildlife biologists and technicians also install watering systems for the cattle that often attract both birds and insects.

Get Involved!

Sign up for the free "Wild Side" newsletter. This e-newsletter helps you stay informed about Oklahoma's nongame wildlife issues and the Wildlife Diversity Program's conservation projects.

- The Tallgrass Prairie

A Glance at the Ecoregion Supporting Oklahoma's Highest Number of Bird Species

- Dominated by four tall, warm-season grasses: big bluestem, lndiangrass, switchgrass and little bluestem.

- Average grass height: 24 to 36 inches.

- Receives about 40 inches of precipitation annually.

Birding Hotspots

- Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve

- Hulah Wildlife Management Area

- Osage Hills State Park

What to Look For

- American golden plover

- Bell's vireo

- Upland sandpiper

- Scissor-tailed flycatcher

- American kestrel

Status of the Tallgrass Prairie Birds

Much like the shortgrass prairie to the west, the tallgrass prairie hosts several true prairie-dependent birds. The large tracts of native range benefit many birds including the greater prairie-chicken. Even so, this grouse has seen dramatic declines in the past 50 years. While the decline has slowed in the past 10 years, biologists are still concerned about the population.

Declines have not been limited to the greater prairie-chicken; several sparrows found in the tallgrass prairie have seen population declines of I percent to 3 percent annually, according to the Breeding Bird Survey. Additionally, the Bell's vireo has seen annual declines of 2.59 percent in Oklahoma since 1966.

Forty-three birds found in the tallgrass prairie are species of greatest conservation need.

Threats to Tallgrass Prairie Birds

Altered Fire and Grazing Regimes: Prescribed burning is an important tool for livestock managers and wildlife managers. While annual burning encourages new growth palatable to cattle, these year-to-year fires, when done on a large scale, can remove habitat for ground-nesting birds.

Invasive Vegetation: Many invasive plant species were planted with good intentions, but some, such as sericea lespedeza, have done more harm than good. Initially planted for erosion control, this plant has created many challenges to birds and other wildlife. Because sericea produces tannins, it is unpalatable to cattle when mature. Without grazing, it can form large stands of thick, woody vegetation. Sericea lespedeza is also a prolific seed producer and can spread very quickly in disturbed areas. Originally, it was thought these seeds would benefit wildlife. Instead, the seeds are too small to provide nutrition to many wildlife species.

Spotlight on Brown-headed Cowbirds

The nomadic brown-headed cowbird once needed an alternate nesting strategy as it followed the herds of bison across the plains. Because of this wandering lifestyle, the female brown-beaded cowbird was unable to attend her nest. Instead, a female cowbird would lay up to 40 eggs a year in the nests of several different bird species while traveling across the plains.

Although the bison herds no longer cover the Great Plains, the brown-headed cowbird still uses this strategy. Only now, this brood parasite has the time to re-visit the other nests to check on her young. If her chick is outcompeting the other specie's young, she travels on to the next nest. But if the host adult pushes out the invading chick, the female cowbird may retaliate by destroying the host nest.

Working for Wildlife: How the Wildlife Department Helps Birds

Rotational Burning and Grazing: The Wildlife Department uses prescribed burning and grazing as a management tool on many of its wildlife management areas. Fire can be used to reduce the amount of litter on the ground, increase forbs (and thereby insects), and manage woody plant encroachment. When biologists rotate sites that are burned or grazed, they create blocks of habitat that vary in size, plant composition and structure. This diversity or "patchwork habitat" allows for the management of a variety of species.

Promote Native Grasses: Most game birds nest in 12to 24-inch-tall clumps of grass that conceal the incubating adult and eggs from predators. Bare ground between individual clumps allows for easy movement and foraging. Introduced grasses such as bermudagrass, tall fescue and old world bluestem can completely cover the ground. This heavy thatch layer can limit movement, reduce the amount of forbs, and make fallen seeds inaccessible to birds.

Get Involved!

Several eagle watches are scheduled throughout the state. For a complete listing of watches each winter, go online to travelok.com

- The Cross Timbers

Jena Donnell/ODWC

Jena Donnell/ODWCA Glance at the Ecoregion Where Trees More than Three Centuries Old Grow

- Dominated by post and blackjack oaks and bluestem grasses.

- Receives about 40 inches of rain a year.

- The cross timbers is a transition between the large eastern forests and the vast grasslands of the plains.

Birding Hotspots

- Lexington Wildlife Management Area

- Chickasaw National Recreation Area

- Lake Thunderbird State Park

What to Look For

- Harris's sparrow

- Painted bunting

- Summer tanager

- Red-headed woodpecker

- Northern flicker

Status of the Cross Timbers

Birds As the eastern deciduous forest gives way to the prairie, a unique ecoregion is formed: the cross timbers. If properly managed, cross timbers habitat can be characterized by well-spaced oak trees with native grasses growing underneath. Historic accounts of this ecoregion vary; some settlers found trees so dense they couldn't "cross through the timber." Others found well-spaced trees that allowed wagons to easily "cross through the timber." This region spreads across central Oklahoma and is home to 117 species of birds.

While development often negatively effects birds, some have adjusted. Even though the cross timbers is one of the most developed ecoregions, several species of "generalist" birds are common to backyard feeders and nest boxes. For example, the house wren has increased 1.42 percent per year in Oklahoma since 1966.

Forty-eight birds found in the cross timbers ecoregion are species of greatest conservation need.

Threats to the Cross Timbers Birds

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Urban sprawl is a leading threat to many birds across the state. Small developments and housing additions are popping up across the countryside, disrupting the native landscape with an increasing number of landscaped yards and improved pasturelands. When native areas are separated by agricultural or urban areas, wildlife may be trapped in small blocks of remaining habitat or may be forced to other suitable areas.

"Perch and Planting" of Eastern Redcedars: Many landowners are familiar with the fast-growing, space-consuming eastern redcedar. Even though these trees can provide wildlife shelter during winter snowstorms, they can also form dense stands and limit the amount of usable space. Some birds are actually helping establish eastern redcedar trees along fencerows, as they sit on a fence and deposit the consumed seeds.

Spotlight on Loggerhead Shrikes

One of the many amazing species found in the cross timbers region is the loggerhead shrike. This small predatory songbird impales its prey on any sharp object found in its habitat, from Osage orange thorns to barbed wire points. These tyrants require dense shrubs or trees to nest, but also need open grasslands to forage for small insects and lizards.

Although marked similar to the northern mockingbird-both are grey and black in color with white wing patches-the loggerhead shrike has a black "mask" covering the eyes and a hook-tipped bill. This bird frequently sits on barbed wire while waiting for its prey to pass by before swooping down for the kill. Once the prey is captured, it is hung out to dry. Insects and lizards often are victims, but shrikes will also impale small rodents.

Working for Wildlife: How the Wildlife Department Helps Birds

Eastern Redcedar Removal: Prescribed fire is the most cost-effective eastern redcedar control method and is used each year on the Department's wildlife management areas. In fact, biologists conducted prescribed burns on more than 80,000 acres in 2014! Fire is most effective on seedlings less than 4 feet tall. If trees are allowed to mature they can form dense, volatile stands with very little fuel underneath. Under those circumstances, normal prescribed fires can be either unsuccessful or extremely dangerous. Instead, mechanical brush management is needed. Though effective, bulldozing can be expensive and can expose large amounts of bare ground. Even though the bare ground is temporary, it can cause erosion and lead to establishment of non-native vegetation.

Get Involved!

Turn your property into a Wildscape! Get tips and plant lists for your region in "Landscaping for Wildlife: A Guide to the Southern Great Plains."

- The Ozark Mountains

A Glance at the Ecoregion with Some of the Oldest Caves and Mountains in the Country

- Dominated by oak-hickory forests, this area is characterized by hills and plains.

- Receives about 42 inches of precipitation annually.

- Extensive underground drainage results in a large number of springs.

Birding Hotspots

- Spavinaw Hills Wildlife Management Area

- J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve

- Cookson Wildlife Management Area

What to Look For

- Bald eagle

- Belted Kingfisher

- Red-eyed vireo

- White-throated sparrow

- White-breasted nuthatch

Status of the Ozark Birds

Because of the similarity to the eastern deciduous forest, the oak-hickory forests of the Ozark Mountains are at the western edge of many eastern bird species. The wooded creeks and rivers are home to a variety of warblers and other birds, including the belted kingfisher. This fish-eating bird nests in tunnels dug into high banks and requires clear streams to catch prey. Unfortunately, this bird has declined nearly 2 percent per year in Oklahoma in recent times.

The Breeding Bird Survey has also documented declines in the red-headed woodpecker, but it shows an increase in other woodpeckers including the red-bellied woodpecker, the downy woodpecker and the ladder-backed woodpecker.

Thirty-seven birds found in this ecoregion are species of greatest conservation need.

Threats to Ozark Birds

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Many forest birds require large tracts of undisturbed habitat. One of the largest threats to these birds is the fragmentation of their feeding and nesting areas. While the conversion of forest to farmland was an initial challenge to these birds, the threat of urban sprawl has become an even larger issue. By fragmenting the habitat, the area can become more susceptible to invasive plant and animal species which can harm native populations.

Spotlight on Nightjars

The name "nightjar" or "goatsucker" refers to a group of eight nocturnal insectivorous birds, four of which are found in North America and Oklahoma: the chuck-wills-widow, whip-poor-will, common poorwill and common nighthawk. These birds are adept at feeding on insects; their wings are shaped for fast flight, their large mouths open in a semicircle, and the modified feathers around the mouth known as "bristles" funnel insects into the mouth. Because nightjars are cryptically camouflaged in varying shades of browns, black and gray, they are very difficult to locate and identify. Once located, they can be distinguished by wing shape, size and the presence or absence of white on the tail feathers. Each of Oklahoma's nightjars can also be identified by its call or song. Like many other birds, nightjars are named for their song; some of which can last up to 40 minutes. Unlike many other birds, nightjars do not lay their eggs in a nest. Instead they make a scrape on the forest floor and rely on their camouflage to avoid predators.

Working for Wildlife: How the Wildlife Department Helps Birds

Hardwood Thinning: Many of our Ozark region wildlife management areas have been removing small hardwood trees to increase the amount of sunlight available on the forest floor. After the canopy is reduced, grasses and forbs gradually replace the dense layer of leaves. This new arrangement provides a variety of species with foraging areas and creates nesting and screening cover for ground-nesting birds.

Get Involved!

Buy a Wildlife Conservation License Plate. Proceeds from the sale of these colorful plates go to the Wildlife Department's Wildlife Diversity Program, which assists more than 800 of the state's wildlife species and the places they live.

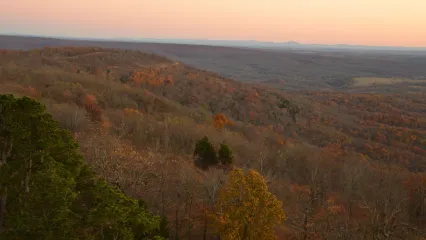

- The Ouachita Mountains

Randall Latham/RPS 2021

Randall Latham/RPS 2021A Glance at the Ecoregion with the Most Rugged Terrain in Oklahoma

- The east-west orientation of this range causes more shady and moist conditions on the north side of the mountains, which yields more hardwoods. The southern slopes are sunnier, drier and dominated by pine trees.

- Receives about 50 inches of precipitation annually.

Birding Hotspots

- Ouachita National Forest

- Red Slough Wildlife Management Area

- Little River National Wildlife Refuge

What to Look For

- American bittern

- Scarlet tanager

- Yellow-throated warbler

- Yellow-breasted chat

- Tree sparrow

Status of the Ouachita Birds

In springtime, the Ouachitas are filled with migrating birds. Some of these birds only stay in the area for a few weeks before moving north, while others spend the summer nesting in Ouachita Mountain forests or swamps. A few of these nesting birds, such as Bachman's sparrow, are restricted to areas of pine forests and are very sensitive to habitat loss. This drab but melodic bird nests in clumps of grass under the pine canopy. Between 1930 and 1960, Bachman's sparrows saw dramatic declines and became a high conservation priority across its range. In recent years, the decline has slowed to 2.61 percent each year in the southeastern coastal plains.

Forty-nine birds found in the Ouachita Mountains are species of greatest conservation need.

Threats to Ouachita Mountain Birds

Nest Invasion by the brown-headed cowbird: Many warblers and other songbirds of this ecoregion are vulnerable to the brown-headed cowbird. As mentioned in the tallgrass prairie section of this article, female brown-headed cowbirds are nest parasites and will lay eggs in a number of other bird nests. (There are more than 220 known host species.) When the eggs hatch, the cowbird chick is often much larger and more vocal. Because of these traits, the host songbird is often tricked into feeding the cowbird chick more than her own young. Birds in fragmented habitats are especially vulnerable to cowbird nest invasion and other threats.

Spotlight on Neotropical Migrants

Birds that summer in North America but winter in South America are often referred to as neotropical migrants. Examples include various species of warbler, tanager, vireo and the scissor-tailed flycatcher, which is Oklahoma's state bird. These migrants travel north from their South American wintering grounds in spring and take advantage of Oklahoma's seasonally abundant caterpillars and flying insects as well as fruits and nectar. Migrants also make the trip to ensure their future chicks have enough food and other resources to survive.

While many environmental factors may signal the best time to migrate, birds rely on changing day length to determine when to start migration. In preparation for the journey, birds go through many physiological changes, including increased lung and heart size.

One way to see these colorful migrants is to set up a backyard water feature. These features provide migrants an important source of water while they pass through Oklahoma on their way to nesting grounds. Water features offer great opportunity to learn about bird behavior.

Working for Wildlife: How the Wildlife Department Helps Birds

Red-cockaded Woodpecker Management: In addition to managing game species, the Wildlife Department also manages for federally endangered species such as the red-cockaded woodpecker. Biologists clean existing woodpecker cavities and remove nest competitors such as flying squirrels and wasps. They also install artificial cavities and put tracking bands on nestling and juvenile birds. Each nest cavity is protected by painted metal plates that prevent enlargement by other woodpeckers. The bases of active cavity trees are wrapped in metal flashing to deter climbing snakes. The Wildlife Department also conducts habitat restoration work by thinning the midstory hardwoods to promote pine regeneration and improve foraging habitat. Prescribed burns are conducted at three-year intervals to control hardwood development and restore the historic pine/bluestem habitat.

Get Involved!

Build your own bluebird box! Providing a nest box for songbirds is one way to help offset the damaging effects of habitat loss. And building your own box is a great way to participate in a conservation activity. It provides a fun learning experience for beginning outdoor enthusiasts! Find nest box building plans for eastern bluebirds and other cavity-nesting birds at noble.org.