Springtime in Outdoor Oklahoma means newborn birds, rabbits, squirrels, deer — and most every other critter that might come to mind. And along with nature’s renewal come the phone calls and messages.

People who encounter young animals call or message the Wildlife Department wanting to know what to do.

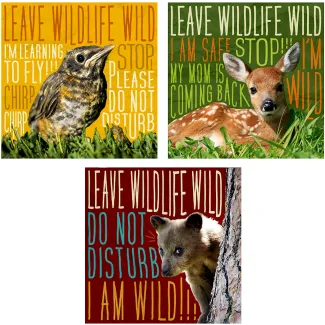

The main message from wildlife biologists to anyone who comes across baby birds or other young animals is this: “Keep Young Wildlife Wild.” That means it’s usually best to leave young wildlife alone, experts say.

Finding a young animal by itself does not mean it’s been abandoned or “needs to be rescued.” Adult animals are often nearby and will visit their young sparingly to avoid detection from predators.

Oftentimes when a young bird or animal is removed from the wild, its “rescuer” quickly realizes he or she cannot properly care for the young creature, and many of those animals soon die in the hands of people just trying to help.

If a young animal has been taken from the wild, it should be returned to the wild as soon as possible, biologists say, even though its chances of survival have been compromised.

There are also legal considerations. Many species of animals are protected by laws that prohibit people from handling them or keeping them in captivity.

So, what can be done if someone runs across newborn birds, bunnies or other animals? Here are some guidelines:

Newborn birds or fledglings: While they might look helpless, they do not need assistance unless they have clear signs of injury, such as a broken wing. If you find a hatchling or nestling (a young bird that has closed eyes and is without feathers) outside the nest, you can try to return it to its nest or create an artificial nest. Contrary to popular belief, the parent birds won’t reject the young bird if you touch it. If you find a fledgling (a young, fully feathered bird) outside the nest, leave it alone. While it is hopping around on the ground, the parents are usually nearby still taking care of it. If you find a fledgling near a road or exposed to danger, you can move it to a safer, sheltered location nearby.

Young rabbits, squirrels, opossums: Even when they appear small, they are able to fend for themselves if they are fully furred and their eyes are open. It is best to leave them alone and keep pets away from them. If these young animals are able to run away, they are able to fend for themselves. Generally, young mammals are visited by their mother only a few times each day to avoid attracting predators to the young. A nest of bunnies will only be visited by the adult female twice per day to nurse the young. The young are generally safe when left alone because their color patterns and lack of scent help them remain undetected. In most cases, it’s best to leave all young animals alone.

Fawns: Late May and early June are the most likely times when people will come across a solitary fawn. The animal might appear helpless, but it’s actually part of the species’ survival strategy. A fawn may be motionless and seem vulnerable, but this is normal behavior, and the doe is probably feeding or bedding nearby. Even if you see a fawn alone for several days, you should still leave it alone. Fawns are safest when left alone because their colors and patterns help them remain undetected. Does visit their fawns to nurse very infrequently, a behavior that helps fawns avoid detection by predators. If well-meaning people repeatedly visit a fawn, it can prolong separation from the doe and delay needed feeding. Fawns will often be left in areas where people might easily find them, because those are places predators might be less likely to visit. If a fawn has already been moved from where it was found, experts recommend to return it to the capture site, even if many hours have passed. The notion that a mother will reject the young after being touched by people is largely a myth.

The Wildlife Department doesn’t have facilities to bring wildlife into any of its offices. But ODWC does certify wildlife rehabilitators who are qualified to care for most injured or truly orphaned wildlife.

Trying to help young wildlife in cases of actual abandonment or injury might be justified. When an injury is apparent, call a licensed wildlife rehabilitator for instructions. And, if after lengthy observation you become certain a young bird or animal has been abandoned or orphaned, call a rehabber for instructions. There is a list of rehabbers on the Wildlife Department’s website at www.wildlifedepartment.com/law/rehabilitator-list.

Another option is to employ a nuisance wildlife control operator (NWCO), who is skilled and educated in handling human/wildlife conflicts. Although permitted and regulated by the Wildlife Department, NWCOs are not state employees. They operate as private businesses and normally charge a fee or solicit a donation for their services.

NWCOs are authorized to capture, relocate, or euthanize nuisance wildlife including snakes, armadillos, badgers, bats (except endangered species), beavers, bobcats, cottontail rabbits, coyotes, fox squirrels, gray squirrels, flying squirrels, gray and red foxes, ground squirrels, jackrabbits, minks, muskrats, nutrias, opossums, gophers, porcupines, raccoons, rats, striped skunks, weasels and woodchucks. And some NWCOs are authorized to manage and control Canada geese.

Leaving nature to its natural cycles of birth, growth, and renewal is an appropriate way to appreciate wildlife. Allowing the natural parents of a young animal to care for their offspring is the best way to ensure healthy development for the young ones.

Many animals produce large numbers of offspring in their lifetime to compensate for losses and for natural predation. An injured animal that dies becomes a food source for other wildlife; it’s best left to its natural course of life and death.

So, if you run across a fawn, rabbit, or other animal alone in the woods, remember that the critter is right where it belongs. It’s best to just walk away and “Keep Young Wildlife Wild.”