Peggy Hill, professor emerita with the University of Tulsa, may be recently retired, but that hasn’t stopped her from continuing to study nature - especially the nature of crickets - or from contributing to science.

After a career dedicated to training high school and college students, and researching prairie insects and other interests, she’s launched herself back into the field by partnering with the Wildlife Department and two former students to learn more about where the rare prairie mole cricket can be found in our state.

The two-inch long cricket, once thought to have disappeared from North America’s prairies, is well adapted to life underground. Their large claw-like forelimbs allow them to dig in the soil and to create burrows from which to call and attract females in spring.

Listening for the male’s call, distinguishable by the chirp frequency and pitch, is the only reliable way to survey the cricket’s whereabouts. But the crickets only call for about an hour at sunset, and only when conditions during their three-month mating season are just right.

Hill was first introduced to the prairie mole cricket in 1991 when she and colleague Harrington Wells conducted listening surveys as part of a larger U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service status review. Very little was known about the cricket at the time, with only two mentions of the insect in scientific literature.

“I was intrigued,” Hill said. “Prairie mole crickets are the largest North American cricket, but so little was known. How can a bug be that big and nobody know anything about it?”

Hill couldn’t resist the challenging puzzle the crickets presented, and began studying a population of crickets calling in the White Oak Prairie near Vinita in northeastern Oklahoma.

“The study area was only 45 minutes from my house, and I would work there every night through the spring period. It seemed anything I learned about these crickets was new. That gave me the freedom to study what I thought was interesting.”

Hill’s work has shed light on many aspects of the cricket’s life, including their intricate mating behavior and how males acoustically tune their burrows to make their calls more attractive. And while she feels there’s still more to learn about their burrow, she’s partnered with Dan Howard and Carrie Hall, both with the University of New Hampshire, to revisit the decades-old survey effort.

“I’ve been wanting to do this survey for 24 years,” Hill said.

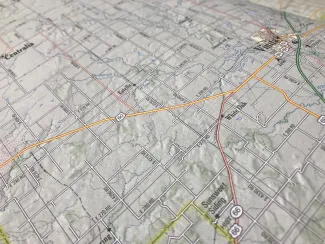

The goal of the survey – just one part of the larger prairie mole cricket project – is to visit as many of the 1989 – 1996 survey routes as possible to see if the crickets are still able to persist in that area.

“I make a travel plan for the night, based on the historic routes, and stop where there’s a safe place to pull off the road to listen for prairie mole crickets. There is so much night noise and so many insects and so many frogs. But if you know what the prairie mole cricket sounds like, you can easily pick out the call from a quarter-mile away.”

Hill documents the presence or absence of crickets at each site, along with the weather and habitat conditions. Though the project has only started, Hill is excited to have found pockets of crickets calling at historic sites.

“My general impression is that crickets will probably still be at a site as long as there hasn’t been a major change in land use. Is there a QT or housing addition on the site, or does it still look like a prairie that would sustain them? If the site looks like it did in 1995, we’ve had pretty good luck finding them.”

Hill’s surveys will continue in 2020 when she plans to use a habitat model developed by former student Kit Keane for his 2016 dissertation research, as well as the predictive models developed as part of the larger study by Howard and Hall at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in Osage County. The hope is to see if the team can find undocumented populations based on suitable habitat found by the computer models. An updated Oklahoma range map will then be created at the end of the study.

“My career really started with the prairie mole cricket. Revisiting sites from my early career, well it’s been a great part of my first year of retirement.”

This prairie mole cricket project is funded by the Wildlife Department’s State Wildlife Grant F18AF00625, with support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the University of New Hampshire, and the University of Tulsa. Learn more about the prairie mole cricket at wildlifedepartment.com.