Within the predator-proof fences of the Tishomingo National Fish Hatchery’s broodstock pond, a large but secretive creature rises from the 30 degree water under the cover of darkness and lumbers onto land. There she begins digging a nest – one of few reasons her species ever leaves the water. Using only her back feet, she slowly excavates a foot of earth from the pond bank.

More than 20 adult alligator snapping turtles are kept in Tishomingo National Fish Hatchery's broodstock pond. Researchers scour the banks of this pond for the turtles' nests each spring and summer.

Two hours later, when her clutch of eggs has been deposited and buried, she slips back into the water and rejoins the other alligator snapping turtles living in the pond.

These prehistoric-looking turtles, fascinating mysteries of a past era, are an essential part of the hatchery’s plan to rebuild a self-sustaining population of alligator snapping turtles across their historic range.

“We wanted to do something before these turtles were gone,” said Brian Fillmore, fisheries biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS).

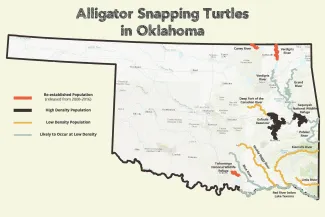

Once found throughout the southern half of the Mississippi River drainage basin, including all of eastern Oklahoma’s major rivers, these turtles have been hit hard by habitat loss and overharvest. To reverse the species’ declining population, the USFWS has partnered with several states to enhance turtle habitat and restock rivers with alligator snapping turtles raised at the Tishomingo-based hatchery.

“Turtles are actually a benefit to our state’s fishery. They primarily feed on older, sick and dying fish, allowing the younger fish to grow and reproduce,” Fillmore said. “For these turtles, the easiest meal is the best meal.

“Alligator snapping turtles are actually omnivorous, meaning they eat both animals and plants. So they also provide ecosystem benefits by eating aquatic vegetation, such as cattails.”

In captivity, alligator snapping turtles that weigh around 100 pounds may eat two fish a day during their active seasons of spring and summer. After summer, consumption drops to one or two fish a week in the fall, and no fish during their winter dormancy.

“We’ve released turtles in Oklahoma, Louisiana, Illinois and Tennessee,” Fillmore said.

More than 1,700 alligator snapping turtles have been reintroduced in the four states as part of the federal program since 2006. Nearly 75 percent of those turtles have been released back into Oklahoma’s waterways.

Nesting season for the turtles in our state begins in May and can continue into June, which means researchers and hatchery staff spend many late spring and early summer mornings searching the grassy pond banks for freshly dug nests, collecting and then incubating the eggs. Once hatched, the turtles are cared for at the hatchery for as long as six years. The young turtles are then distributed to conservation partners for their restoration efforts.

This turtle head-start program is proven; studies show alligator snapping turtles released at 4 to 6 years old are 2.5 times more likely to survive than those released at 1 or 2 years old. The larger size of older turtles plays a leading role in the increased survival rate; they weigh more than three times that of the younger turtles, and their carapaces are about one-third longer. Even so, 4-year-old turtles weigh in at just shy of a pound and are only 4.5 inches in length.

While these young alligator snapping turtles have a better chance of survival, it will be several years before they begin contributing to the population.

“These turtles typically reach sexual maturity when they’re between 10 and 15 years old. They’re probably about 25 to 30 pounds at that age,” Fillmore said.

“These are long-lived turtles, perhaps reaching 75 or 100 years.”

The head-start program’s first turtles – 13 adult females and three adult males – came to the hatchery in 1999 from Sequoyah National Wildlife Refuge, about 160 miles east of the hatchery near Vian, Oklahoma. Since these early beginnings, hatchery biologist have been steadily improving their rearing techniques with a series of careful experiments. Adult turtles from other populations have also been brought in to maintain the broodstock’s genetic diversity.

“Eighteen years later, we have around 40 adult broodstock turtles and 1,500 juveniles at the hatchery,” Fillmore said.

From Small Eggs to Large Snapping Turtles

Each of the 1,500 juveniles currently growing in the hatchery got their start as a small egg buried in the bank of the hatchery’s broodstock pond.

Denise Thompson, a doctoral candidate at Oklahoma State University, has been digging these eggs from the pond banks for the past seven years, partnering with the hatchery to learn more about the turtles’ developmental processes and reproductive success.

Denise Thompson and Brian Fillmore prepare to take freshly excavated eggs to the hatchery.

Thompson finds turtle nests the morning after the eggs are deposited by looking for fresh scrapes a few feet above the water’s edge. She then locates the nest entrance, a small tube that leads to a football-size bowl, but drawing an imaginary “X” between the divots created by the turtle’s front and back legs.

Before she opens the nest with her index finger, she confers with Fillmore.

“This is the most important part of the process,” she said with a wink. “We like to guess how many eggs are inside.”

Once all guesses are in, with Thompson predicting 36 eggs, she starts scooping mud from the entrance. Three-and-a-half inches down, she uncovers the first egg: a white, semi-pliable, pingpong ball-sized egg, partially covered with mud. Once by one, the eggs are transferred from the nest to a waiting container. Minutes later, the nest is empty, and 37 alligator snapping turtle eggs are ready to be cleaned, cataloged and stored in the incubator for 90 days. Inside the hatchery, Thompson begins her daily monitoring routine. Each egg’s development is recorded along with the temperature and humidity inside the incubator. Three months later, hatchling turtles begin to emerge.

“A day-old alligator snapping turtle weighs between 15 and 20 grams,” Fillmore said. Thirty hatchlings are needed to make one pound.

Immediately after hatching, each turtle is cleaned, dried and then tagged with a unique code that allows researchers to identify the individuals. “The tags were originally designed for tracking bumble bees,” Fillmore said. “Two drops of superglue on the shell typically hold the tags for two years.”

Immediately after hatching, the young turtles are marked with temporary tags originally designed for bumble bee research. The numbered tags, seen here as light blue circles, help researchers identify this 1-year-old turtle.

Before the temporary tags fall off, a more permanent PIT tag – short for Passive Integrated Transponder – is inserted into the turtles’ hind leg. This allows researchers to identify recaptured turtles with a scanner while in the field, much like a lost pet can be identified. With the tag number ,the researchers will be able to track the turtle’s history, all the way back to the egg.

Thompson is also tracking each turtle’s pedigree. “We started a pilot study three years ago to determine which female, and which male, produced each individual egg. This year, I’ll be learning the identity of the mother and the potential fathers of each nest.”

“Now we’ll be able to quantify how many hatchlings each male has contributed to our population,” Thompson said. “We can also see if any patterns emerge that will tell us which parents produce the healthiest juvenile turtles.”

While Fillmore and Thompson continue their work to produce and track the turtles raised at the hatchery, they’re also hoping to reach a program milestone this year.

“It’s very possible the turtles hatched in 2002, 2004, and 2005 will be nesting this year,” Fillmore said, referring to the first batches of alligator snappers produced and released by the hatchery. “That would be the ultimate success.”