Many outdoor enthusiasts long for the chance to own and manage land for wildlife recreation and, whether the property is large or small, knowing what to do or where to start can be incredibly important to help in achieving the desired goals.

Now, it’s important to note that a landowner’s goals can vary widely, as well as the management options. Spending time on the property to learn of its features and discover “what’s out there” is a good first step and, when managing for wildlife, is important and/or a priority. From there, setting goals and developing an easy-to-follow wildlife habitat management plan are vital.

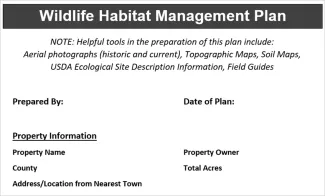

In its simplicity, a good wildlife habitat management plan helps summarize the historic and current state of the property and outlines a plan for the months and years ahead. A management plan also helps narrow down the species that are desired and provide a framework of recommendations to employ. Trying things and hoping for the best may work in some cases, but having a plan with specific management actions and goals will help save money and time long term. These plans are also important for identifying issues and challenges that exist or may arise, and how these should be considered or addressed as management decisions are made. Compromising non-wildlife land goals with wildlife goals is often outlined within the plan too.

Another important part of a good wildlife habitat management plan is a thorough evaluation of the plant communities and habitats across a property. In essence, wildlife management is plant management. In other words, plants – along with water and space – are what provide the food and shelter that game and non-game species need for survival.

Choice food and cover will be highly attractive to the species we hope to see, especially if the food and cover we manage for will meet their year-round needs. Unfortunately, sometimes we see what we believe to be a plush, attractive plant community that wildlife far and wide should be using for their day-to-day needs, but this isn’t always so. Not all plants and plant communities hold the same value, and a healthy arrangement of quality habitats across a landscape can be the difference between higher wildlife numbers in an area, or lower. Identifying limiting factors is a main benefit of a good plan so these can be addressed through sound management.

Of course, a perplexing question that can arise after a property is purchased for wildlife is “where to begin?” Nearly all state and federal wildlife agencies have biologists dedicated to serving private lands, and the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation has biologists that cover the entire state. Biologists from non-governmental organizations and private wildlife consulting agencies are also great resources. Reaching out to one or more is a great place to start and, many times, multiple entities work together to get a landowner going in the right direction.

Some projects may even qualify for cost-share funding which can be a great way to get more done for less. However, funding pools are usually limited and the demand very high. As a result, it’s always good to start early in the planning process and inquire about funding opportunities a year or more ahead of any planned habitat project. Seeking funding through multiple agencies is also a good strategy as each program may have slightly different funding levels, application deadlines, or management options. I will say, though, that double dipping (getting reimbursed for the same habitat work on the same acres by multiple agencies) is not applicable should a landowner receive multiple contracts. So, if you have recently bought a property, or are planning to, thinking about and writing down your goals is important. Taking stock of “what’s out there” is also a great first step to see what may be missing or in short supply based on your goals for the land. And if you're at all in doubt, reach out to one of our ODWC Private Lands Biologists to set up a free technical assistance visit to get another set of eyes, hands, or thoughts to help get you started on the path to your dream property.